Indira Gandhi endgame: What impelled her to call elections?

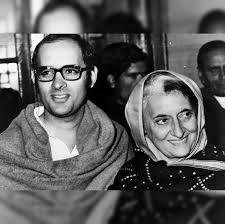

In the turbulent political history of India, few events stand out as starkly as the Emergency imposed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from 1975 to 1977. Even more remarkable, however, was her sudden decision to lift the Emergency and call for general elections in January 1977. This move puzzled many observers at the time and continues to raise questions. Why would a leader, ruling with near-absolute authority, risk everything at the ballot box?

To understand the motivations behind this dramatic decision, one must examine the political, personal, and global factors that shaped Indira Gandhi’s thinking during this critical juncture in Indian democracy.

Context: The Emergency Era

On June 25, 1975, Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency under Article 352 of the Indian Constitution, citing internal disturbance. This followed a ruling by the Allahabad High Court that found her guilty of electoral malpractice and rendered her 1971 election victory void. With the opposition demanding her resignation, Gandhi took the extraordinary step of suspending civil liberties, arresting political opponents, and imposing press censorship.

The Emergency lasted 21 months and altered the political fabric of India. Over 100,000 people were imprisoned without trial. The infamous sterilization campaign spearheaded by her son Sanjay Gandhi, the demolition of slums in Delhi, and rampant misuse of executive power created deep public resentment. Yet, Indira Gandhi ruled with complete control. So why did she risk relinquishing that power?

1. The Illusion of Popularity and Control

A key reason for her decision was a misplaced confidence in her popularity. Surrounded by loyalists and with the opposition silenced, Gandhi believed that the Emergency’s “discipline” and “efficiency” had won public support. Her administration touted increased train punctuality, reduced crime, and economic stability as signs of good governance.

Censorship ensured that the press only echoed government narratives. Dissent was muted, and citizens, out of fear, were reluctant to voice criticism. This echo chamber led Gandhi to believe that she had successfully reshaped the political landscape in her favor.

2. Internal and External Pressures

While Gandhi exercised tight control, there was discomfort even within her own party. Many Congress leaders and bureaucrats were uneasy about the continued suppression of civil rights. Some quietly advocated for a return to normalcy, fearing long-term damage to India’s democratic institutions.

Internationally, India’s reputation was at stake. Western democracies, including the United States and the United Kingdom, criticized the suspension of democratic processes. Indira Gandhi, who had once championed the Non-Aligned Movement and democratic socialism, was now seen as an authoritarian figure. By calling elections, she hoped to silence foreign critics and restore India’s democratic image on the global stage.

3. Legal and Judicial Signals

There were also growing murmurs within the judiciary about the legal basis and longevity of the Emergency. Several habeas corpus petitions had been filed, and although the Supreme Court had upheld the government’s position, dissent within legal circles was growing. Continuing the Emergency indefinitely could have eventually triggered a judicial confrontation or mass protests.

Calling elections provided a way out without facing legal or constitutional crises. It was a calculated move to maintain control through democratic legitimacy rather than emergency powers.

4. A Political Masterstroke—or Misstep?

Some analysts believe Gandhi viewed the elections as a tactical move. If she won, she would have constitutional backing to continue her reforms and silence critics. If she lost, she could step back temporarily and rebuild.

However, this political gamble underestimated the depth of public anger. Voters, particularly in northern India, had borne the brunt of forced sterilizations and evictions. The opposition, although fragmented at first, united under the banner of the Janata Party, bringing together leaders like Jayaprakash Narayan, Morarji Desai, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and L.K. Advani.

The 1977 elections became a referendum on the Emergency. In a dramatic reversal, the Congress Party was swept aside in key states, and Indira Gandhi herself lost her seat in Rae Bareli.

5. The Democratic Paradox

Ironically, the very democratic institutions Gandhi had tried to suppress ensured her peaceful exit from power. The decision to call elections, while miscalculated, showed that even authoritarian leaders might return to the ballot when they believe they can win. It also underscored the resilience of Indian democracy, which withstood one of its greatest tests and emerged stronger.

Historians still debate whether Gandhi’s move was one of arrogance, naivety, or a sincere belief in her political popularity. Regardless of intent, it marked the end of one of the darkest chapters in Indian democracy—and the beginning of a political awakening among the Indian electorate.

Conclusion

Indira Gandhi’s decision to call elections in 1977 was driven by a combination of overconfidence, political calculation, and international pressure. She believed she could regain popular legitimacy and reinforce her grip on power through democratic means. But in doing so, she misread the national mood and underestimated the impact of the Emergency’s authoritarian policies.

The results were both historic and humbling. India witnessed the first non-Congress government at the center, and a powerful message was sent: even the most powerful leaders are accountable to the people. In retrospect, her decision to call elections remains a paradox—a democratic act that ended an undemocratic period.